Saving Solomon Islands' Forests, One Protected Area at a Time

Lessons learned by CEPF grantee NRDF

17 August 2020

The Solomon Islands—an archipelago made up of six islands east of Australia—is known for its dense tropical forests. But as a result of logging and mining, that’s changing, and it’s changing fast.

Conservationists are in a race against time as international companies—mostly from Malaysia who then supply the Chinese market—convince remote tribes in the Solomon Islands to trade the resources on their land for cash. But, more and more, local people are discovering the price they are truly paying for this exchange.

Deforestation often leads to undrinkable water and the hampering of other ecosystem services that Solomon Islanders depend on. The local biodiversity—much of which is found nowhere else on Earth—is jeopardized, too.

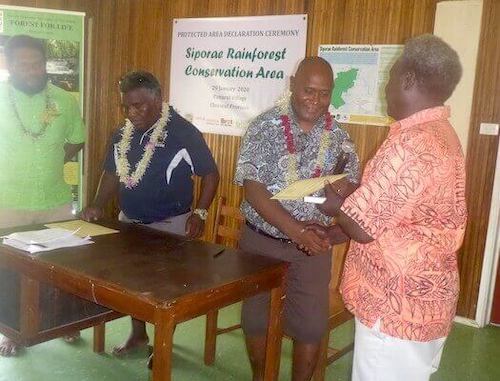

One way a tribe can safeguard its land is through protected-area designation. The process, however, is long and bureaucratic. That’s where CEPF grantee Natural Resources Development Foundation (NRDF) comes in. The locally based organization helps tribes on Choiseul Island navigate the many steps involved.

To establish a protected area, neighboring tribes must be consulted to ensure land boundaries are agreed upon. Next, a management plan and management committee must be established. Various government ministries must then sign off.

Finally, public notice is given, allowing others the opportunity to object. In NRDF’s experience, someone almost always objects, leading to additional time and expenses related to hearings by the local chief or courts.

Thus far, NRDF has successfully assisted two tribes in establishing their land as protected areas with three more in the pipeline. Here’s how they’ve overcome the challenges encountered along the way:

Challenge: Convince people to protect their land.

The process to designate land as a protected area takes two to three years to complete. Logging and mining, on the other hand, “are very attractive because they will give money to a tribe immediately,” said NRDF Project Manager Wilko Bosma.

Solution: Don’t try to convince them. Let them come to you.

NRDF doesn’t approach tribes to find out if they’re interested in pursuing protected-area designation. Instead, tribes reach out to them.

“You need to have the right leader who is the driver and is our constant contact at the village level,” said NDRF’s Stephen Suti. “The leader must be motivated and have the support of key people within the tribe.”

The land, too, must be appropriate and fit within what NRDF prioritizes. If funding is coming from a CEPF grant, the area must fall within a Key Biodiversity Area. Because NRDF has limited capacity, areas whose remoteness prevents frequent visits are also not considered.

If NRDF feels that they aren’t likely to be successful—either because of a lack of commitment from the tribe or because of the location of the land—they will turn down the request. Instead, they will point the tribe to other NGOs that may be able to assist or provide general advice on how to proceed in establishing the protected area on their own.

Challenge: Navigating local bureaucracy.

There are many government groups that NRDF must work with to have the protected area approved—the Ministry of Environment, Climate Change, Disaster Management and Meteorology; the Ministry of Forestry; and the Ministry of Lands, among them. The provincial government must be consulted, too.

“Working with all of these ministries, in our experience, creates a whole lot of headaches,” Bosma said. “The government is committed to PAs, but they are keen on logging as well because it is one of the major revenue earners for the country.” The government takes a 25 percent share of log export sales.

Solution: Establish strong relationships with government officials.

“You really need to have someone who knows all of these ministries inside out,” said Bosma. For NRDF, that person is Suti.

“I’ve worked for 16 years in the forestry sector, and I did some consultations with most of these ministries, so I have a close relationship with them,” Suti said. “You have to have skills in persuasion. Not corruption, but speaking from the heart.”

NRDF’s efforts help the government achieve its target of 10 percent of land designated as protected areas. “The ministries see that NRDF is the arms and the legs in the field, helping to achieve this target,” Bosma said.

Challenge: Facing a formidable opponent.

As a tribe waits for its protected-area designation to be approved, the lure of fast cash from loggers and miners can be a continual temptation. One tribe NRDF worked with was at the final stages of gaining protected-area status when the chief ultimately decided to take money from loggers instead.

“The whole area now is gone to logging,” Suti said.

Solution: Find appealing alternative livelihoods.

NRDF helps counter the logging and mining money a tribe loses out on by working with them to develop ways to earn income from the land sustainably.

“The tribe can choose for themselves what livelihood they want to engage in,” Bosma said. “We focus on creating a regulated income and making sure they invest [the money] in a good way.”

NRDF has begun working with the community-based Nakau Programme to provide Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES) crediting.

“The Nakau Programme is already working in Fiji and Vanuatu,” Bosma said. “We have connected to a buyer, so the demand is there.”

Looking Forward

The pressure from mining and logging isn’t likely to go away until the last tree has fallen, but the alternative—protected-area designation—is picking up steam.

“We have many other tribes within the Solomons asking for our help,” Bosma said. “Hopefully other organizations can take the model we’ve developed and replicate it elsewhere.”