Main menu

Main menu

CEPF is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the European Union, Fondation Hans Wilsdorf, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan and the World Bank.

Visitez le site français コア情報の日本語翻訳を読むOr use Google Translate to translate the English site to your language:

GTranslate

This week begins the UN Biodiversity Conference in Egypt, where many of the world’s biggest wildlife conservation champions come together to discuss the challenges of protecting biodiversity and work to develop solutions.

One focus during this year’s event: How to “mainstream biodiversity into the sectors of energy and mining, infrastructure, manufacturing and processing, and health.” In other words, how do we work with companies in these industries to minimize the disruption they cause to ecosystems. (The issue falls under Aichi Target 2.)

Many of CEPF’s grantees are working to address this exact challenge, including efforts to work with the extractive industries such as oil, gas, mining and quarrying.

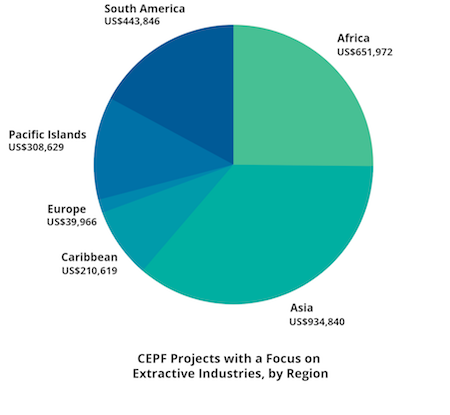

CEPF has funded some 20 extractive-related projects across eight biodiversity hotspots. In Myanmar, part of the Indo-Burma Biodiversity Hotspot, CEPF grantee Fauna & Flora International (FFI) has had tremendous success in mainstreaming biodiversity into policies, plans and business practices.

Plants and animals have adapted and evolved to Asia’s unique karst landscapes where limestone rock—eroded and dissolved over millennia—has been shaped into dramatic peaks and extensive caves. Today, many species are so unique that they are found only on one hill or in a single cave system. (In 2018, FFI discovered a whopping 21 new fish species in Myanmar, and 19 gecko species were discovered in the country’s karst hills the year before.)

These ecosystems aren’t only important to biodiversity; they’re important to the cement, industry, too. Limestone is a common ingredient in cement, and karst landscapes have plenty of it.

During extraction of limestone from the earth, damage to the ecosystem and the species on which it depends can be limited if certain guidelines and best practices are followed.

One momentous achievement was a 2016 stakeholder workshop, hosted by FFI, that brought together, for the first time in Myanmar, government agencies, cement companies, local conservation organizations and development banks. The workshop resulted in a radical change in awareness of limestone-related biodiversity among participants. At the event's conclusion, Shwe Taung Cement Company asked to work with FFI, which assisted the company with its biodiversity management plan and offset strategy for its limestone quarry. "This is the first biodiversity management plan and offset strategy ever done by a Myanmar cement company," said FFI's Frank Momberg.

The initial CEPF grant closed at the end of 2016 and a second began the following April. FFI and its myriad partners—departments of mines, forestry and environment; cement companies; environmental impact assessment companies and practitioners; and karst biodiversity experts—have submitted best practice guidelines to the Environment Department to be included in regulations and guidelines. FFI is also working to complete an assessment of Myanmar's karst Key Biodiversity Areas and recommend those with high biodiversity and endemism for protected area designation.

Economic sanctions in Myanmar have recently been lifted. The cement market in the country is booming—several new cement factories are planned or starting construction—making FFI's efforts well timed and more important than ever.

In nearby Vietnam, PanNature is tackling similar challenges by strengthening the skills of local journalists who can then focus public attention on the environmental impacts of the country’s increase in development, which is converting forest for industrial plants and infrastructure.

In the Eastern Afromontane Biodiversity Hotspot, Forest of Hope Association is discouraging illegal mining in Rwanda’s Gishwati-Mukura National Park and improving legal mining operations on the park’s borders, helping decrease sediment in nearby Lake Kivu, a priority freshwater Key Biodiversity Area.

Meanwhile oil and gas companies in Uganda have been given the legal right to extract resources from within Murchison Falls National Park. Wildlife Conservation Society is working with these companies to mitigate as much damage as possible and protect the myriad wildlife found in the park.

“Extractive companies often need to plan for the long term: 20, 40, even 100 year investments,” said CEPF’s Managing Director Jack Tordoff. “These are similar timeframes that conservation and restoration of natural ecosystems is concerned with. By engaging constructively with extractive companies, CEPF grantees are developing long-term solutions.”